Lawyers and Doctors for Human Rights

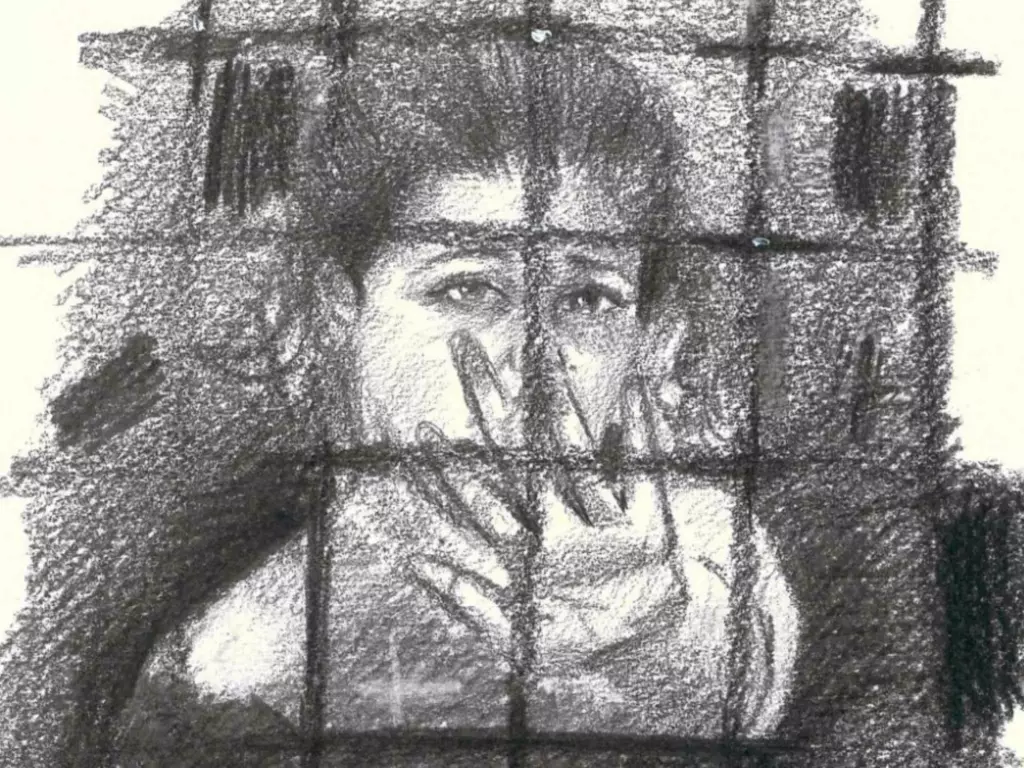

Lawyers and Doctors for Human Rights (LDHR) in Syria used practice-based knowledge from legal and medical practice to document patterns of child sexual violence in government detention centres. Drawing on firsthand survivor testimonies, medical-legal documentation, and psychological assessments, their work brought visibility to a hidden, overlooked, and under-researched form of child sexual violence.

Key themes

Children deprived of liberty, whether in conflict with the law, in immigration detention, in psychiatric institutions, or state-run care, face elevated risks of sexual violence. However, they are often invisible in research. Ethical constraints, restricted access, and political sensitivities make it extremely difficult to collect reliable data from these settings.

In these settings, practitioners who work directly with affected children possess critical practice-based knowledge grounded in firsthand experience, long-term trust, and engagement with victims and/or survivors. Their insights offer rare visibility into childhood sexual violence risk patterns, mechanisms of harm, and contextual barriers to reporting or redress.

What these case studies show

These case studies illustrate how practice-based knowledge (PbK) is used in real world settings to improve childhood sexual violence prevention and response. Each case focuses on what practitioners or survivor-led groups learned through action, reflection, and decision-making in their own contexts, and how that knowledge was taken forward.

What these case studies do and do not do

The case studies do not aim to produce generalisable findings. Instead, they offer context-specific insight into how practice unfolds, where challenges emerge, and how actors respond in real time. The absence of evaluation or impact data should not be interpreted as evidence for or against effectiveness.

How to use these insights in your own work

These case studies are intended to support reflection rather than replication. Readers may find them useful for:

- identifying questions to explore within their own practice

- recognising patterns or tensions that resonate with their own settings

- anticipating practical, ethical, or institutional challenges before they arise

Ethical use and limitations

Documenting and sharing PbK requires careful attention to safety, consent, power, and potential harm, particularly when engaging with sensitive experiences of child sexual violence. The ethical principles guiding this work are set out in the PbK Guidance Framework

Scope and limits of the knowledge shared

Each case study reflects the type and depth of knowledge available within its context. Differences in format, detail, and focus reflect variation in purpose, access, and the conditions under which knowledge was documented and shared.

Content warning

Some of the case studies include details of childhood sexual violence. Each case study includes specific content notes to support informed engagement. Please take care of your well-being as you read and step away if needed. For additional support, you may find it helpful to consult the following resources:

- Brave Movement, Practicing Self-Care

- Sexual Violence Research Initiative (SVRI) Dare to Care: Wellness, self and collective care for those working in the Violence against Women (VAW) and Violence against children (VAC) fields

Context

Since the start of the Syrian conflict in 2011, Lawyers and Doctors for Human Rights (LDHR) noted how detention and torture have been systematically used by the government as tools of political control. Children, along with adults, have endured prolonged detention under extreme conditions, including torture, forced labour, and sexual violence. Because detention facilities operate in secrecy and survivors face stigma and risk of retaliation, sexual violence against children has remained largely undocumented.

The political sensitivities of the conflict, restrictions on access to detention centres, and high risks of retaliation have made it nearly impossible to conduct formal research. Prevalence data are scarce, and most forms of evidence have been blocked by the conflict context. Children subjected to sexual slavery in detention were not only invisible in terms of research but also lacked effective advocacy, protection, and support services.

LDHR, a network of Syrian legal and medical professionals, has worked for years to document violations, including those against children in detention. By building trust with survivors and former detainees, they have begun understanding the extent of sexual violence and laid the groundwork for recognition of sexual slavery as a practice in detention.

From insight to action

What was learned from practice-based knowledge

Through survivor testimonies, clinical interviews, psychological assessments, and medical evaluations, LDHR generated knowledge that brought new forms of abuse to light:

- Emerging form of abuse – sexual slavery: Practice-based knowledge revealed sexual slavery as a systemic and previously unrecognised form of childhood sexual violence in Syrian detention.

- Patterns of abuse: Children were subjected to forced labour combined with sexual violence, repeated abuse by guards, and coerced sexual acts under threat of further violence or death.

- Survivor-centred insights: Survivors described continuous, systemic abuse and the mechanisms of coercion that sustained it, making visible the scale and persistence of violence.

- Barriers to reporting and support: Practice-based knowledge surfaced the obstacles survivors faced in seeking justice or care, including fear of retaliation, stigma, absence of safe reporting channels, and lack of access to services.

Real world impact

How practice-based knowledge was shared

- Childhood sexual violence in detention

LDHR examined grave violations against children, including torture, arbitrary detention, and sexual violence. Based on 10 medical evaluations, they published a report revealing that four in five detained girls were subjected to childhood sexual violence and three in five boys experienced forced nudity. Survivors and witnesses corroborated repeated abuse, including coerced sexual acts, harassment, and continuous threats of violence.

- Childhood sexual violence in the form of sexual slavery in detention

In 2022, LDHR published a second comprehensive report sharing their practice-based knowledge – specifically documenting sexual slavery against adults and children in Syrian detention centres. The report was grounded in medical evaluations conducted by LDHR doctors trained under the Istanbul Protocol [1] providing clinical validation of survivors’ accounts and demonstrating the systemic nature of abuse.

The reports aimed to:

- Inform advocacy: Provide credible documentation for international justice mechanisms.

- Raise awareness: Highlight under-recognised forms of childhood sexual violence in closed settings, especially conflict zones.

- Support survivor-centred care: Recommend tailored responses for service providers and legal actors to address the specific needs of survivors of detention-related sexual slavery.

LDHR’s work demonstrates how practice-based knowledge can create foundational knowledge in environments that are difficult to access. While the impact of these efforts is still unfolding, the documentation serves as a critical step in setting the stage for future interventions, advocacy, and research. Since Syria has been liberated from the regime since December 2024, LDHR is now exploring more opportunities to expand the study.

Why this matters: The value of practice-based knowledge

LDHR’s work underscores the crucial role of practice-based knowledge in revealing abuse that remains hidden in environments that are typically inaccessible to researchers. By drawing on firsthand survivor accounts and medical-legal documentation, LDHR provided critical knowledge can provide the foundation for immediate intervention as well as long-term research priorities.

If you're working in a similar context

LDHR’s experience in Syria shows how practice-based knowledge can surface forms of violence that remain hidden in formal research, especially in closed or politically sensitive environments. These questions are offered to guide reflection in your own setting:

- Unseen violence: Are there forms of harm affecting children in your context that remain unacknowledged or undocumented because of secrecy, stigma, or political risk?

- Safe documentation: What safeguards are needed to ensure that survivors and those gathering testimonies are protected from retaliation or retraumatisation?

- Trusted knowledge holders: Who already holds credible knowledge of these harms, and how might their perspectives be included in shaping advocacy and response?

- Revealing systems: What gaps or silences in institutional responses could practice-based knowledge in your context help bring to light?

Sources

- Lawyers and Doctors for Human Rights (LDHR). (2019). No silent witnesses: Violations against children in Syrian detention centres. Lawyers and Doctors for Human Rights.

- Lawyers and Doctors for Human Rights. (2022). “Dying a thousand times a day”: Sexual slavery in Syrian detention. Lawyers and Doctors for Human Rights.

- United Nations. (2022). Istanbul Protocol: Manual on the effective investigation and documentation of torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment (Rev. ed.). Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. https://www.ohchr.org/en/publications/policy-and-methodological-publications/istanbul-protocol