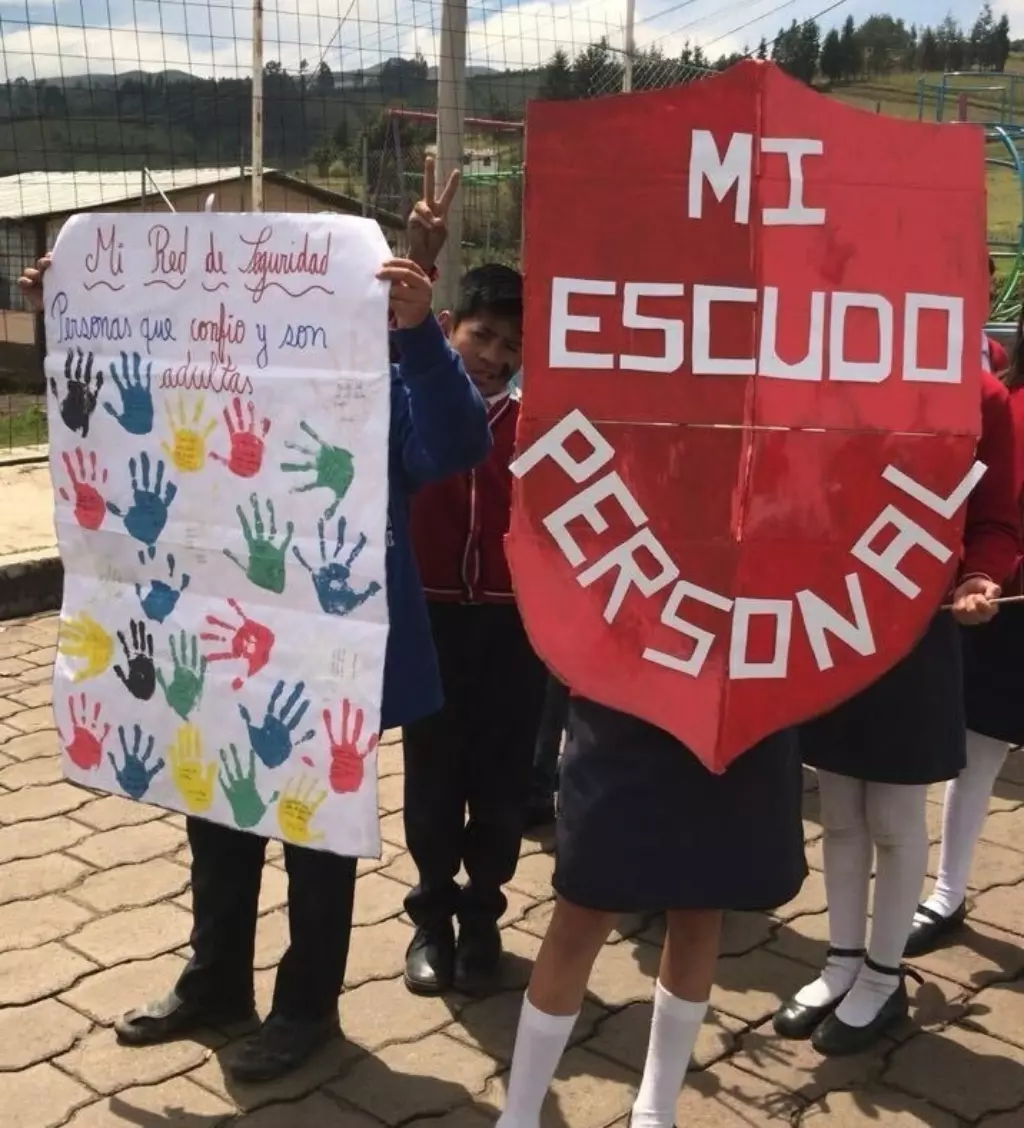

Transformation and renaming to “Mi Escudo”

Following the positive results of the pilot program “I Have the Right to Feel Safe” (2016–2017), Fundación Azulado launched a comprehensive redesign to turn the intervention into a more structured, scalable, and sustainable tool.

In 2017, a specialized consultancy was carried out in collaboration with the design group Komité to transform the original manual into a series of structured, play-based activities aligned with the program’s learning and protection objectives.

This transformation included:

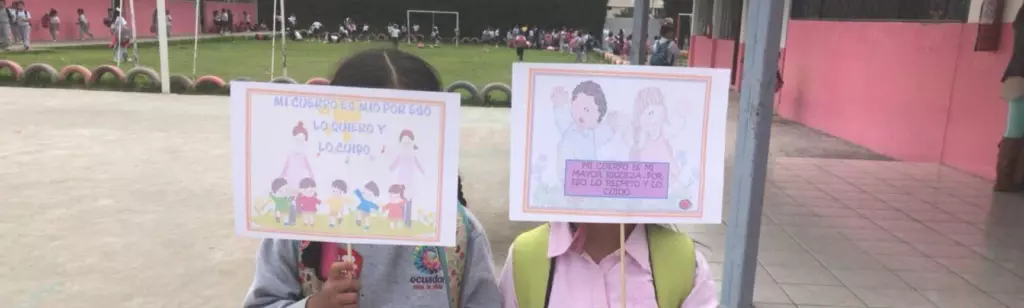

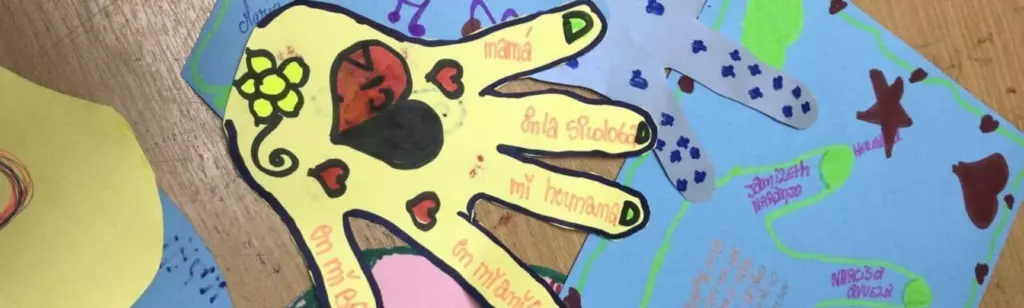

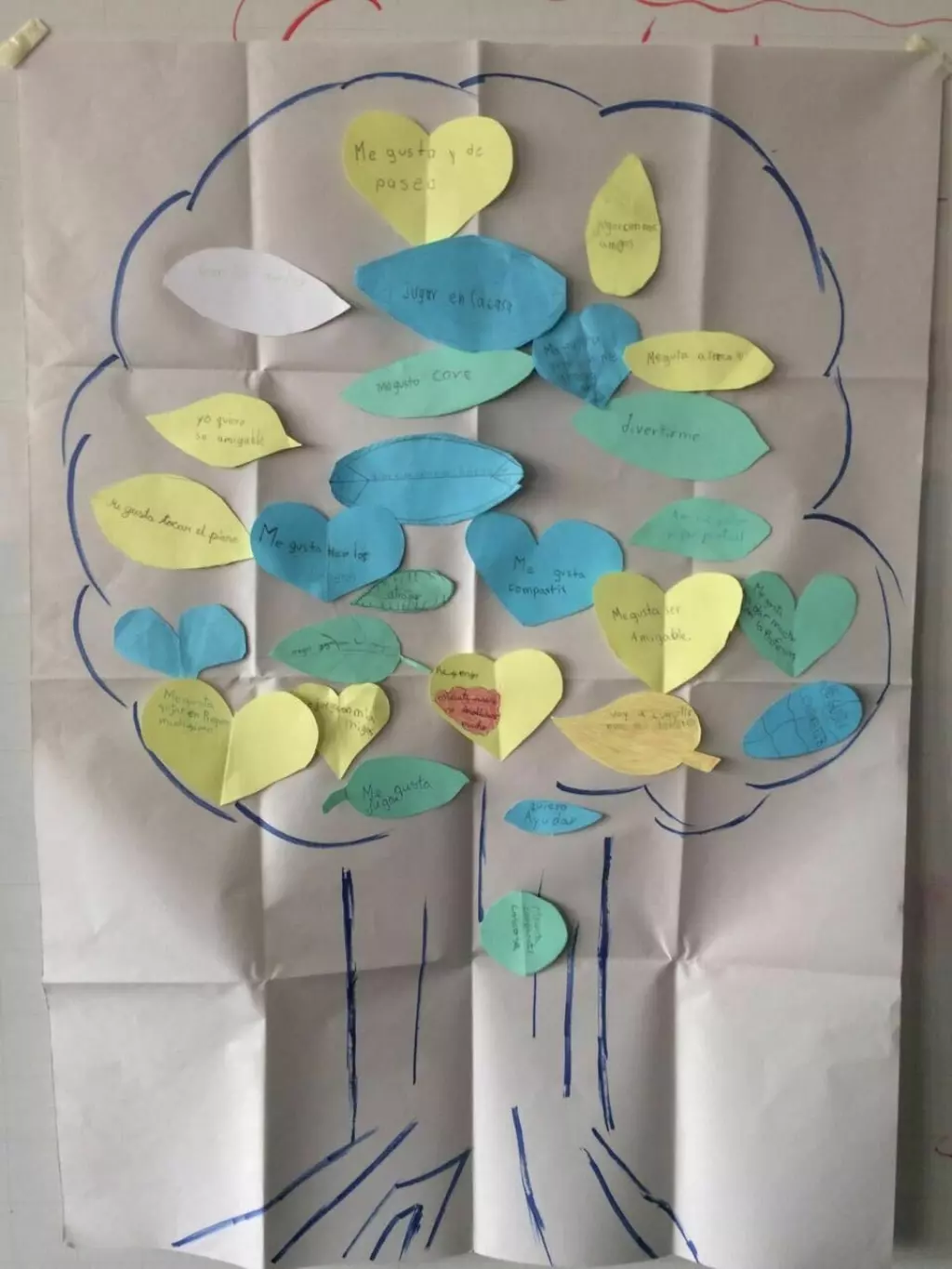

- Designing 12 structured, game-based sessions focused on key topics such as self-esteem, personal boundaries, secrets, private body parts, emotional identification, trusted networks, and self-protection strategies.

- Aligning each session with educational and child protection objectives and compiling them into a School Toolkit, which included a teacher’s manual, interactive student workbooks, and visual aids.

- Developing a train-the-trainer model to strengthen teachers’ and school counselors’ capacity to implement the program independently and consistently in classrooms [5].

The development process took about a year, including curriculum design, technical validation, field testing in rural and urban schools, and printing materials.

As a result, the team renamed the program “Mi Escudo” (My Shield) to reflect a child-friendly metaphor of personal protection and empowerment.